International legislation

Motivation

The collection and exchange of plant genetic resources is highly regulated and any scientist and practical plant breeder needs to know the basic rules of the exchange of genetic resources between companies.

In the following the broad historical context and the key regulations will be presented.

Learning goals

Historical trends in intellectual property legislation

The exchange of genetic resources is closely linked to the protection of intellectual property. The legislation of intellectual property is an incentive by providing financial returns for investments. An inventor gets exclusive rights for a period of time, and the society gets a stimulus by competition through the publication (disclosure) of inventions.

1 One could argue that the discovery of the Americas by Columbus started the first period of globalization.

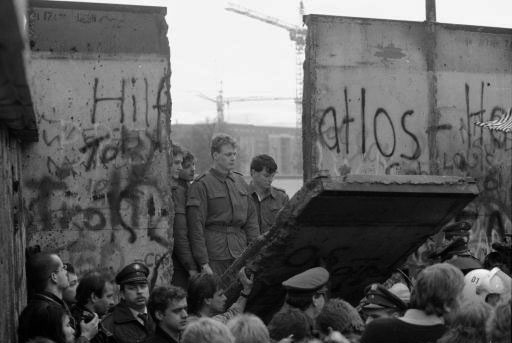

Since 1989, the in which the Berlin Wall was broken down and the era of the Communist Empire ended (Figure 1}, there have been numerous historical developments that also affected agricultural science and economics. Progress in science led to the origin of plant biotechnology. The importance of the private sector was increasing and this also affected food, pharmaceutical and seed companies. The collapse of the Communist empire opened new markets in the former communist countries. This situation led to the development of new free-trade agreements and new international treaties regulating the exchange of goods and intellectual property. In hindsight, this period is now the second phase of globalization. The first period of globalization driven by colonialism of European empires peaked around 1900 (and ended with the First World War).1

The Convention of Biological Diversity

Motivated by the recognition of a global environmental crisis, a large international conference on the environment was organized. At this UN Environmental Conference in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD)2 was signed, which became effective in 1993 (Figure 2).

In article 1 of the convention it is declared that each country is responsible for the conservation of its own biodiversity. Other aspects of the convention are to promote the sustainable use of its components, a fair and equisharing of benefits originating from exploiting biodiversity, and the appropriate access and transfer of relevant technology.

In article 15, it is declared the states have sovereign rights over their natural resources, and that this includes the possibility to legislate the use of these resources.

Articles 16 and 17 regulate the licensing of proprietary technology, the sharing of research and development research, as well as the training on using biodiversity and the protection of biodiversity.

Revisions of plant variety protection

In Europe, the protection of plant varieties as intellectual property is regulated independently from patents. However, the rapidly evolving field of plant biotechnology and other developments made a revision of PVP necessary.

Two key key terms in plant variety protection (PVP) are

- Farmer’s exception:

- Farmers have the right to maintain to store seeds for their own use.

- Breeder’s exemption:

- Breeders are allowed to use registered varieties as sources of initial variation to create new varieties.

Plant variety protection (PVP)

Since the 1960s international rules and guidelines for plant variety protection were developed by the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV)4 with its headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland (Figure 4).

National legislations and international treaty (UPOV convention) were developed first 1961, modified to the current version in 1978, and with most recent modifications in 1991. One consequence of these modifications was to limit farmer’s exemption. Farmers still had the right to save seeds to plant future crops and to sell seeds, but now only the saving of seeds is allowed.

Breeder’s exemption was maintained with the following exemptions:

- Extend protection to essentially derived varieties (EDV): ‘although clearly distinguishable from the initial variety, conforms to the initial variety in the expression that result from the genotype’.

- can be obtained by selection of natural or induced mutants, somaclonal variants, backcrossing, genetic engineering, etc.

- For self-pollinated varieties, F1 hybrid varieties, and tuber-propagated varieties

- Requires deposit of seed sample

“Patents on Life”

In response to the developments in biotechnology, a new principle originated: Intellectual property can be granted for living organisms or biological processes under certain conditions and and with several consequences.

This development, however, led to discussions whether patents for life should be allowed: One question discussed was, for example: Can living organisms or biological processes be patented if the are not novel nor non-obvious?5

5 For a definition, see Wikipedia

After the second World War, it became obvious that there was a general decline in agricultural diversity, to a large part fostered by the industrialization of agriculture and the consequences of the Green Revolution. Would an increase in patented varieties contribute to such a decline?

Will there be a shift to crops with a major commercial value, because they provide a higher return on investments than minor crops?

In this context, one concern is that patents may limit national economic and social development strategies. For example, many countries currently only allow patents on processes but not products (the latter being made available through “compulsory licensing”). Such a policy induces national industries, through reverse engineering to develop own products. The biotechnology industry based on patents can compete in world market for substitutes of natural products: sugar, cocoa, plant oils

The patenting of biodiversity was discussed in the context of bioprospecting versus biopiracy. It raises the issue how to reward not only inventors (recipients of biodiversity) but native farmers and indigenous people (donors of biodiversity)?

The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources (ITPGRFA)

History

In the context of the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) it was decided that a special agreement for agricultural cropsis required. This resulted in the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA, Plant Treaty, International Treaty) under the responsibility of the FAO.6

After the resolution 7/93 of CBD to develop the plant treat, seven years of negotiations followed. The aim of the negotiations was to Define a CBD conform, multilateral use of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture (PGRFA). The international treaty became effective as from 29 June 2004 with 123 signatory states including DE, FR, EU and USA. Currently, the treaty has 148 contracting parties (i.e., countries that ratified the treaty).7

Content of the Plant Treaty

The full text of the plant treaty is under this link. In the following the key aspects of the treaty are summarized.

Articles 1,2,3,10

Subject matter: Plant genetic resources for food and agriculture: Any genetic material of plant origin of actual or potential value for food and agriculture

Multilateral system: To facilitate access to plant genetic resources for food and agriculture, and to share, in a fair and equiway, the benefits arising from the utilization of these resources, on a complementary and mutually reinforcing basis.

Article 12.2

The Contracting Parties agree to take the necessary legal or other appropriate measures to provide access to other Contracting Parties through the Multilateral System.

Article 12.3d (Conditions for access)

Recipients shall not claim any intellectual property or other rights that limit the facilitated access to the plant genetic resources for food and agriculture, or their genetic parts or components, in the form received from the Multilateral System.

Interpretation of intellectual variety protection

The European Union interprets Article 12.3.d of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources as recognising that plant genetic resources for food and agriculture or their genetic parts or components which have undergone innovation may be the subject of intellectual property rights provided that the criteria relating to such rights are met.

Similar positions are taken by individual countries: Germany, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Sweden, United Kingdom

Access to plant genetic material

Article 2.4 states that the access to plant genetic material will be facilitated under the terms and conditions of the Standard Material Transfer Agreement (SMTA). The SMTA was decided in resolution 1/2006 of the Governing Body of the ITPGFRA (16 June 2006). The SMTA comprises ten articles and four annexes.

The standard material agreement[^7] has 10 articles and 4 annexes. The first four articles provide the general dispositions, which are briefly summarized in the following.

Article 1: Parties

Provider and Recipient are contract partners in case of signature.

Shrink wrap: The MTA is accepted if the material is received by mail and the parcel with the seeds is opened.

Click wrap: The MTA is acceptance via mouse click, e.g., during the ordering process.

Article 2: Definitions:

Available without restriction: A product is considered to be available without restriction to others for further research and breeding when it is available for research and breeding without any legal or contractual obligations, or technological restrictions, that would preclude using it in the manner specified in the Treaty.

Product: Plant genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture ready for commercialization in contrast to Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture under Development

Article 3:

Subject matter, to define in Annex 1 of the SMTA.

Article 4:

General dispositions, e.g., the governing body determines the third party beneficiary, which is the FAO.

Article 5: Obligations of the provider

The provider grants access to

- plant genetic resources

- its passport data

The provider respects intellectual property rights and notifies the governing body.

Article 6: Obligations of the recipient

Use only for purposes of food and agriculture and do not use for non-food/feed industrial uses.

Make non-confidential biological data and material and material available to the multilateral system:

- under the conditions of the MTA

- and the notification of the governing body

Commercialization of a product that is not available without restriction:

Flat rate licence fee of 1.1% of sales - 30% to FAO (exhaustive)

Licensing of a product that has been developed on the basis of plant genetic material of the multilateral system:

Flat rate licence fee of 1.1% of sales to FAO (exhaustive)

Option to reduced payments:

Flat rate licence fee of 0.5% of the licence fee to FAO (non exhaustive)

Benefit-sharing fund of the ITPGRFA

In order to distribute the payments made by the ITPGRFA, a benefit-sharing fund was established in 2008. All licensing fees are paid into this fund and additional money has been paid into this fund by governments. With the funds, projects between farmers, breeders and scientists to conserve plant genetic resources are funded.

More information about the activities of the fund can be found at http://www.fao.org/plant-treaty/areas-of-work/funding

Article 7: Applicable law

This article describes which rules of law apply to the SMTA:

- International commercial law (UNIDROIT)

- Dispositions of the Standard Agreement

- Decisions of the Governing Body

Article 8: Dispute settlement

Article 8 describes how disputes are settled.

The interested parties are provider and recipient, and the FAO as third party beneficiary.

In case of disputes between provider and recipient, there is an obligation to inform FAO as the third party beneficiary.

A three step dispute settlement mechanism was developed:

- Amicable dispute settlement

- Mediation by a mutually agreed mediator

- Arbitration: Parties determine court mutually, otherwise a procedure with the international chamber of commerce. The governing body proposes a list of potential arbitrators

Effects of the SMTA on research

The SMTA is a compromise between free access to plant genetic resources ("open source biology") and intellectual property

Universities have access to plant genetic resources and its biological data. But there is an obligation to inform the governing body about the results of the research.

The seed industry has access to plant genetic resources and its biological data. There is legal certainty about the use of plant genetic resources and a dispute settlement mechanism. However there is also a flat rate licence fee, which may be substantial for economically successful varieties created with plant genetic resources, and there is an obligation to inform the governing body about the results of the use of plant genetic resources.

The Treaty viewed from a breeder’s point of view

Which aspects of the plant treaty are relevant for a practical breeder. The main source of information is the website of the plant treaty, which contains the text of the treaty and information about the practical implications of the treaty.

There is a training module on the plant treaty, which provides guidance on the implications for the different stakeholders.8

In the following there are a few questions breeders may ask about the importance and roles of a treaty:

- Does the plant treaty and the sMTA cover all crop species? If not, where do I have to look it up?

- Do I have to sign an MTA if I receive seeds from a US national genebank because the US did not sign the treaty?

- I want to order seeds from a US national genebank. The accession I want to order was collected in a country that was has signed the treaty. Do I have to sign an sMTA with the US genebank or with an institution in the country of origin?

- Does the sMTA make a difference between research use of genetic resources and the use in commercial plant breeding?

- Does it make a difference in the sMTA if I use the material for conventional plant breeding or for genetic engineering?

- Do I have to sign an sMTA if I am working with a German plant breeding company and order material from a German gene bank?

- Do I have to sign an sMTA if I collaborate with a plant breeding company in a developing country who will send seeds to me (based on a mutual countract) for commercial variety development?

The Nagoya Protocol

It was thought that there needs to be an extension to the CBD for the access to genetic resources not covered by the ITPGRFA

The official title of this agreement is the Nagoya protocol on access to genetic resources and the fair and equisharing of benefits arising from their utilization to the convention on biological diversity

The Nagoya protocol came into action on the 12. October 2014 after the 50th state ratified the protocol.

Obligations of the Nagoya protocol

The Nagoya protocol defines three obligations:

- Access to plant genetic resources

- Benefit sharing

- Compliance

In order to obtain access, users seeking genetic resources need to get permission from the provider country. Provisions under the Nagoya protocol go beyond the CBD to provide greater legal certainty. Local and indigenous communities (LICs) have an established right to grant access to resources under their control and management.

To ensure benefit sharing, providers and users must negotiate an bilateral agreement on benefit sharing.

A system will be put in place to ensure compliance with access and benefit-sharing (ABS) requirements using internationally recognized certificates of compliance.

The basis of the Nagoya protocol is prior informed consent, and an valuation of local and indigenous communities (LICs) and their traditional knowledge.

There will also be an ABS clearinghouse that will share information on ABS.

Issues with the Nagoya protocol

Since both the International Treaty (ITPGRFA) and the Nagoya Protocol deal with genetic resources, there is some interaction and possible conflict between both legal regulations.

What are key differences?

The ITPGRFA deals with genetic resources and establishes a multi-lateral system for benefit-sharing.

The Nagoya protocol deals with everything else (biodiversity and genetic diversity of crop plants (not in Annex 1 of ITPGRFA) and all other species (all of biodiversity!), and requires a bilateral agreement on access and benefit sharing

This creates some, as yet unresolved issues:

- Where to draw the line for genetic resources of crops and their wild ancestors?

- Within countries different organisations are responsible for ITPGRFA and Nagoya Protocol. Conflicts between the institutions may ensue.

- There may be the interest to put close relatives of crops under the Nagoya protocol for better access sharing.

Stakeholders and potential areas of conflicts

At a discussion meeting in 2014, different stakeholder groups met and exchanged their views with respect to both ITPGRFA and the Nagoya protocol. The results of the discussion are summarized in a discussion paper.

In the following, some statements of the stakeholders are presented.

Global Crop Diversity Trust

The global crop diversity trust9 is an international organisation to promote the conservation and use of crops and their wild ancestors. It is based in Bonn, Germany.

9 <www.croptrust.org>

They organise the process to regenerate seeds and send duplicates to other genbanks and make the available under the multilateral system of the ITPGRFA.

The crop trust state that the ITPGRFA has not been (completely) implemented in many countries.

They collected wild relatives of Annex 1 (of the ITPGRFA) crops and make them available for research and breeding. The collection is carried out with national partner organisations.

International seed federation

The federation an international organisation of plant breeding companies. It describes the current situation as follows:

The lack of legal certainty is of great concern: Which rules apply?

Which body administers requests for genetic resources? Competent authorities in the different countries are still frequently not present.

There is a lack of coordination between authorities within and between countries

Overall the breeding sector prefers a multilateral system for access and benefit-sharing

A general problem: Administrators involved in PGR exchange and benefit sharing need to understand that modern crops have complex pedigrees with hundreds of ancestors indentifiable in their ancestry. As a consequence, the marginal value of each ancestors needs to be recognized and taken into account in the benefit-sharing process.

Scenarios for the utilization of plant genetic resources

In the discussion meetings the participants discussed many scenarios for use of genetic resources under the ITPGRFA and the Nagoya protocol to identify potential areas of conflict (Halewood, 2015).

- Scenario 1:

- A startup company requests genetic resources of sorghum from a genebank to breed bioenergy sorghum.

-

- Sorghum is an Annex 1 crop under ITPGRFA

-

- But resources will be utilized non-food/feed use, which is not covered by ITPGRFA

-

- Therefore consider request under Nagoya protocol

Scenario 2:

A recipient genetic resource materials under the SMTA and conserved copies of this material. A third party knows about this and requests to send out some of the conserved coopies under the material.

Possible solution: The SMTA requires recipients to send out conserved copies of the material.

Many other interesting cases were discussed.

Future topics for scientific research and political decisions

The ITPGRFA and the Nagoya protocol offer some important issues for scientific research:

- Plant taxonomy and systematics may be required to address the question of whether a plant species is a direct ancestor of a crop

- Which crops will be part of Annex 1? How ist this decided?

- Is the multilateral benefit-sharing system working and is it fair? How are the funds distributed?

- Which type of material is affected by the Nagoya protocol?

Key concepts

| \(\square\) Benefit sharing | \(\square\) Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) | \(\square\) International treaty |

| \(\square\) SMTA | \(\square\) Nagoya protocol | \(\square\) Plant variety protection |

| \(\square\) Farmer’s exemption | \(\square\) Breeder’s exemption | \(\square\) Patent law |

Summary

- After the breakdown of the Berlin wall, many new regulations for the exchange of genetic materials and the protection of intellectual property were implemented.

- The most important regulations are CBD, TRIPS, ITPGRFA and the Nagoya protocol.

- The interactions between these regulations can be quite complex and is far from being resolved.

- In the context of plant genetic resources, the benefit-sharing aspect is very important.

Further reading

- Official website of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Ressources for Food and Agriculture: http://www.planttreaty.org

- Moore and Tymowski, Explanatory Guide to the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK 2005.

Review and discussion questions

- Not all crop plants are included in the International Treaty. What determines whether a crop is included or not into the treaty? Can you think of arguments why or why not a crop is included in the treaty?

- What is the function of Annex 1 of the International Treaty?

- Does the Nagoya protocol apply to plants that can be used as food?

Problems

Genetic diversity of tef

Tef (Eragrostis tef) is a grass species mainly cultivated in Ethiopia and known for its nutritious grain. Assume that your master thesis project is to characterise the genetic diversity of tef using a seed collection that will be sent from Ethiopia to Hohenheim. Before project start, some have to be fulfilled:

- Why does the legal procedure defined by the Nagoya protocol and not by the International Plant Treaty for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA) have to be used here? Justify your answer.

- What are the most important regulations and conditions for the exchange of seeds under the Nagoya protocol?

- Using the tef material you make a discovery that you patent and want to use for starting a company.

- What do you have to do to get the required legal permission for using this material by your company? (A general description is sufficient).

Collection of wheat genetic resources

Scenario: You are conducting a research project on wheat genetic diversity at a research institution. The research involves accessing and using a wheat seed collection from an international genebank. Wheat is an Annex 1 crop under the ITPGRFA.

- Which multilateral legal framework governs the access and exchange of wheat seeds, and what key documentation is required?

- What rights and obligations does the provider (genebank) have under this framework, and how must you (the recipient) fulfill your obligations?

- During your research, you identify a valuable genetic trait that you want to incorporate into a new commercial wheat variety. What steps must you take to ensure compliance with the ITPGRFA, especially regarding intellectual property rights and benefit-sharing?

Drought resistant sorghum varieties

A global food company is planning a joint venture with an agricultural research institute to develop new drought-resistant sorghum varieties. They intend to use both wild relatives and cultivated sorghum lines collected from several African countries. Sorghum is listed in Annex 1 of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA).

What potential challenges could arise when accessing and using these sorghum genetic resources under both the Nagoya Protocol and the ITPGRFA, given the multilateral vs. bilateral approach to benefit-sharing, conflicting legal frameworks, and the interests of various stakeholders?

Consider the following points:

- Stakeholder Conflicts:How do differing stakeholder interests (countries of origin, researchers, food companies) affect compliance and benefit-sharing?

- Overlap and Confusion Between Treaties: How might the overlap between the Nagoya Protocol and the ITPGRFA create uncertainties in accessing genetic resources?

- Benefit-Sharing and Intellectual Property Rights: What are the specific challenges related to balancing intellectual property rights with fair and equitable benefit-sharing?

- Traditional Knowledge and Community Rights: How does the consideration of traditional knowledge and the rights of local communities complicate the process?

- Why is a good biological taxonomy (e.g., based on phylogenetic analysis) for crop plants and wild relatives important in this context?